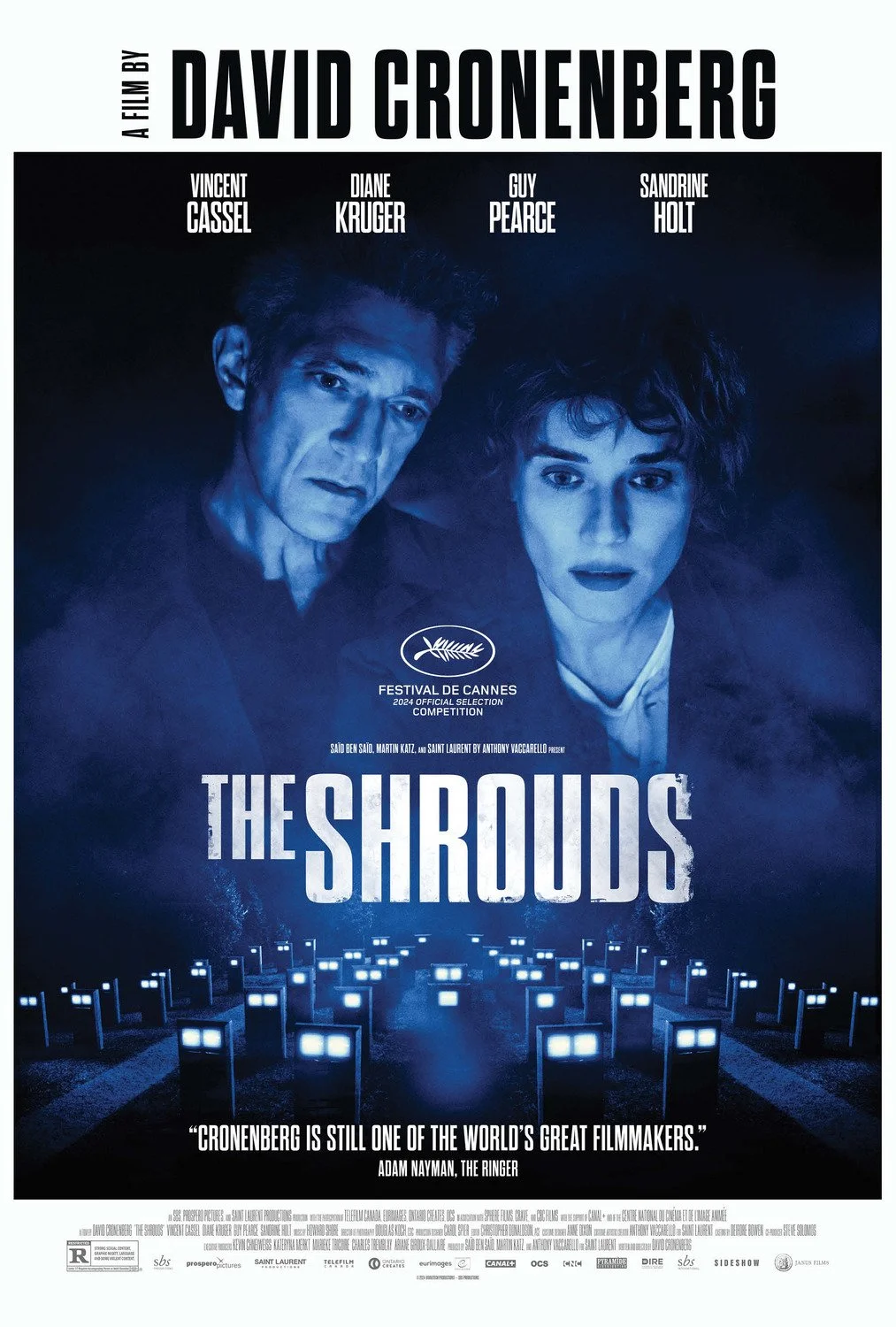

Movie Review : The Shrouds (2024)

There was a time when Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg shocked audiences with his movies. I’ve seen thirteen of them, but I’ve always refused to watch The Fly, because I find the premise too revolting to even consider. I already fucking hate bugs, so I’m not going to spend two hours watching horrifying mutant ones. While Cronenberg’s films have remained visually striking throughout his career, they’ve also grown increasingly and awkwardly personal over the last twenty-five years.

The Shrouds feels like his most personal film yet, even though it tackles the most universal subject he’s ever written about: death. It’s about mortality in the abstract, yes, but it’s also about what it means to die in a world that never forgets, never lets go, and quietly archives every trace you leave behind.

So, The Shrouds follows Karsh Relikh (Vincent Cassel), an aging tech bro who responds to the death of his wife Becca (Diane Kruger) by inventing a new kind of funerary shroud. One that allows the living to monitor the slow decay of their loved ones in real time. It’s a business venture disguised as a coping mechanism, a way of maintaining control over a loss that refuses to be managed.

When the cemetery where Becca is buried is vandalized and Karsh’s company becomes the target of unseen digital threats, his carefully engineered systems begin to collapse. Suddenly, he finds himself subject to forces he can’t predict or influence, reduced to something like a conscious corpse: still moving, still thinking, but no longer in charge of his own trajectory.

The Science of Surrender

Now, if you’re thinking that paying a monthly fee to watch your dead relatives rot in real time is fucked up, you’re not wrong. What’s truly off-putting about Karsh Relikh, however, is that he doesn’t appear to have any particular fascination with death itself. He isn’t obsessive, and staring at his wife’s decomposing body doesn’t seem to provide him with pleasure, arousal, or even catharsis.

His problem is simpler than that and, like every heterosexual white man throughout history, he’s the one insisting on making it more complicated than it needs to be. Karsh Relikh simply cannot let go of his dead wife.

There’s a scene where Karsh puts on a shroud himself. One that, in an earlier David Cronenberg movie, would almost certainly have veered into something erotic or deviant. Instead, he’s quickly reprimanded by his AI assistant, a moment that feels like a quiet but firm refusal by the writer-director to go there anymore. The transgression is identified, then immediately neutralized. Desire is acknowledged, but it’s no longer indulged.

It’s hard not to notice that Vincent Cassel bears an uncanny resemblance to Cronenberg in The Shrouds, and it’s equally hard not to read Karsh as an orchestrator figure rather than a traditional protagonist — someone who builds systems to manage chaos, only to discover that systems don’t grieve on your behalf. Cronenberg’s wife, Carolyn, died from illness in 2017, and unlike many of his earlier characters, Karsh feels uncomfortably close to the man who created him. Not as a stand-in, exactly, but as a partial confession.

As mysterious and apocryphal as The Shrouds remains, it’s tempting to read it as Cronenberg being unusually straightforward with us. Not by offering answers, but by staging surrender in a world that has become increasingly unknowable. Where you never quite know who’s watching, who isn’t, or what any of that information is ultimately for. Whether Cronenberg fully understands the ending himself almost feels irrelevant. That uncertainty is the point. The Shrouds is a film where the unconscious is allowed to surface into material reality only when it’s absolutely necessary and never a moment sooner.

About That Ending

A lot of people have left The Shrouds and will continue to leave it scratching their heads. I won’t spoil the ending here, though I could: it’s abstract enough that without context it would barely register as information. Instead, it’s more useful to look at the character of Soo-Min (Sandrine Holt), who functions as Karsh’s negative image.

Blind and married to another aging tech mogul on his death bed, Soo-Min is someone who has never exercised control until illness forced her to. Where Karsh builds systems to manage grief, Soo-Min becomes a conduit for it. She doesn’t dominate information; she allows it to pass through her. And it’s precisely by surrendering control — by accepting limitation rather than resisting it — that she acquires something resembling power.

I choose to believe that this is how the final scene should be read. That Karsh isn’t dead, dreaming or hallucinating. That by letting go, he finally crosses the hard boundaries he’s devoted his life to mastering. Something genuinely unknowable is taking place on that plane. One of those experiences you spend the rest of your life wondering whether it truly happened or not. Karsh gets more than he bargained for, and what it ultimately means is left to him to decide. Not you. Not me. Not even David Cronenberg.

*

The Shrouds feels like a film made by an old man who’s furious that he still doesn’t know what any of this ultimately means and I mean that in the best possible way. It’s cerebral, controlled, and restrained, even as none of its characters seem to have the slightest idea of what the fuck is actually happening. That tension isn’t a flaw” it’s the point. The film’s truth lies in accepting that our obsessive search for meaning may itself be against nature, a reflex we can’t stop even when it keeps failing us.

You really have to like David Cronenberg to get anything out of The Shrouds and luckily for him, I do. This is not a movie for the uninitiated. Trying to ease someone into Cronenberg with The Shrouds would be like introducing Metallica through Load: not the best, not the worst, but it would be impossible to understand unless you were already there.

7.6/10

* Follow me on Instagram , Bluesky and Substack to keep up with new posts *