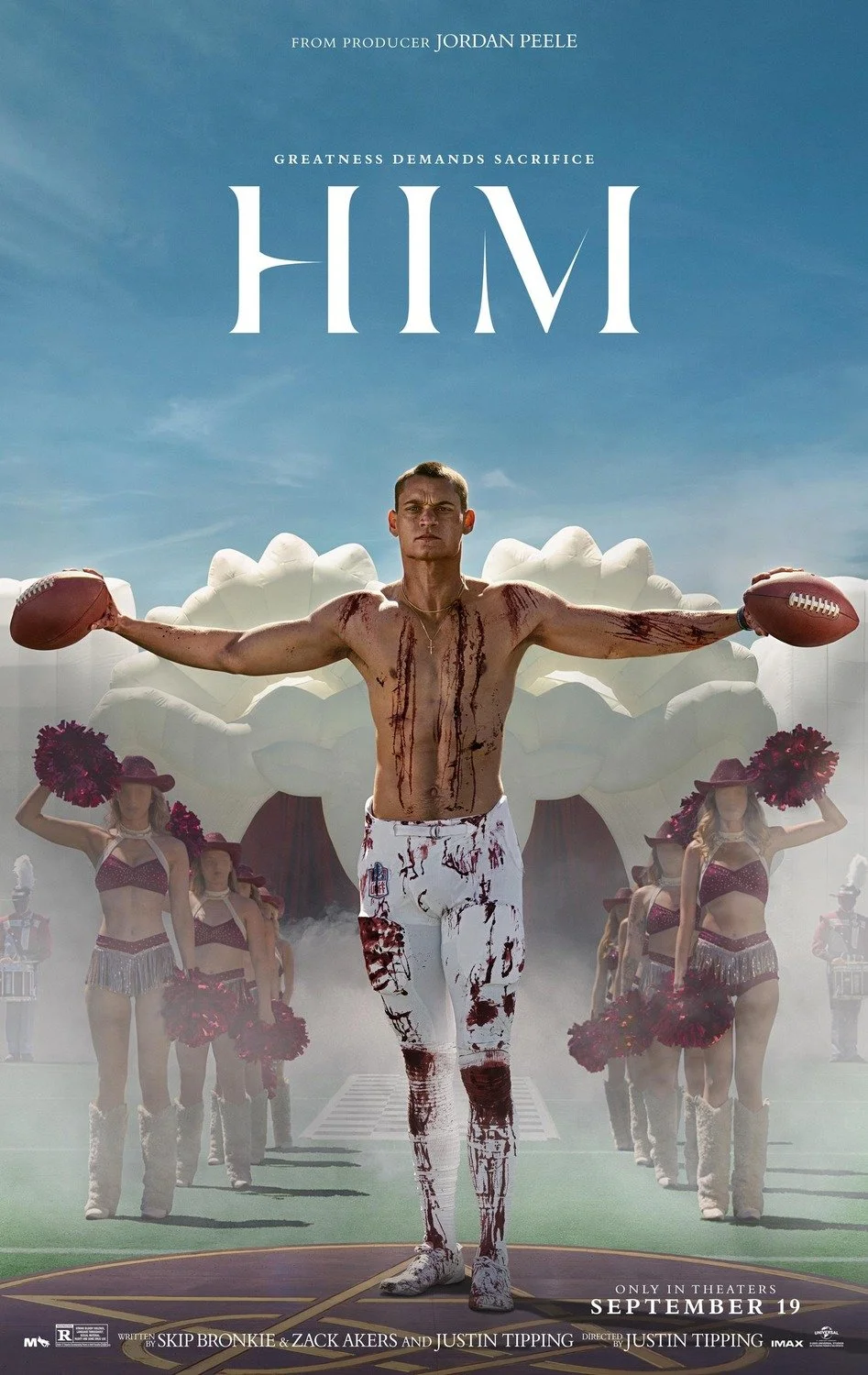

Movie Review : Him (2025)

Being a Super Bowl winning quarterback is, in American culture, roughly equivalent to being a Stanley Cup winning hockey player in Canada: it’s not just a job achievement, it’s the ultimate symbol of status. You don’t do that thing, you become that thing. Even people who actively resent professional sports tend to concede that elite athletes operate as a kind of secular royalty, living proof that meritocracy might still exist if your knees cooperate and your parents made the right early-life decisions.

We already know the cost of entry. A thousand documentaries have mapped the physical pain, the emotional erosion, and the slow replacement of a human personality with a brand logo. So the idea of tackling this same subject through horror, of literalizing the psychological terror of greatness, felt intriguing or at least ambitious. Him was positioned as that movie. It arrived with buzz, cultural curiosity and the vague promise that it might finally say something new about ambition, masculinity, and American worship rituals.

Then it came out, and almost immediately flopped. What happened? I watched Him so you don’t have to and the answer is both simpler and stranger than you’d expect.

Him follows Cameron Cade (Tyriq Withers), a preternaturally gifted young quarterback projected to go high in the not-the-NFL draft, right up until the day he’s inexplicably brained after practice by a man in a costume. The incident leaves him with brutal post-concussion symptoms and a career suddenly balanced on a medical technicality. He ghosts the combine, disappears from the approved narrative and becomes the kind of prospect that sports television pretends not to notice.

Despite this, Cameron is invited to work out privately with his idol, Isaiah White (Marlon Wayans), a legendary quarterback who has won eight not-the-Super Bowls and now exists in a rarified mental space where success curdles into something feral. White is predictably bonkers — less a mentor than a guru — and the movie wastes no time suggesting that whatever is wrong with Cameron’s brain may be the least troubling thing he’s about to inherit.

Jordan Peele's Waterloo Moment

Him is definitely not boring, but it’s bad for boring reasons. This isn’t a glorious failure or a fascinating mess, it’s the unmistakable product of a film that’s been aggressively recut by an anxious producer and that producer is almost certainly Jordan Peele. His name hovered so closely over the project that many people (myself included) assumed he had directed it, which now feels less like a misunderstanding and more like a marketing strategy that backfired.

The evidence is all on screen. The movie is incredibly short (93 minutes), it rushes past major character development like it’s late for another appointment, and it relies on silence and montage where actual conversations should exist. It’s paced like a prestige music video, which is another way of saying it moves fast without ever feeling urgent. You can sense the outline of another movie buried underneath this one. A longer, messier, more committed version if that’s even possible.

Cameron doesn’t even get injured playing football. He gets clocked in the head by a man in a goat suit, which would feel symbolically rich if the movie were actually about concussions. But it isn’t. The injury functions less as a thematic entry point than as a narrative loophole. An excuse to destabilize reality without committing to what that destabilization is supposed to mean.

Structurally, Him behaves more like a cult horror film: a young man isolated from his support system, drawn into the orbit of a charismatic authority figure and slowly transformed by proximity alone. The concussion angle lingers in the background as Cameron repeatedly wonders whether he’s hallucinating what’s happening to him. He isn’t. Which suggests that the movie’s core claim is that a combination of brain damage and peer pressure turns you strange and violent.

That’s not incorrect, exactly. It’s just underwhelming. The world did not need a horror movie to explain CTE, and Him never pushes that idea far enough to become either disturbing or illuminating. Instead, it settles for a vague medical dread that feels less like a revelation than a disclaimer.

Style Over Substance, But It Is Stylish

You know a movie isn’t working when you can explain why it doesn’t with a single platitude. Him is style over substance. That said, the style is doing real work. This is a good-looking movie, and it occasionally convinces you that appearances might be enough.

Isaiah White’s compound, in particular, is immaculately designed to feel untethered from reality. A place that exists outside of time, consequence and ordinary human behavior. It signals not just wealth but a total disconnection from day-to-day life, the kind that turns success into a private mythology. In that sense, it’s arguably the most important character in Him. The space constantly shifts, reacts to Cameron on its own terms and seems to enforce its own logic, independent of whoever happens to be standing inside it.

If you’re feeling generous or chemically adventurous, there’s even a smoked-up argument to be made that the compound itself drove Isaiah insane. Both metaphorically and functionally: an environment so insulated and self-confirming that reality eventually loses its authority. It’s the one idea in Him that hints at something genuinely unsettling, which may be why the movie never quite knows what to do with it.

The technotronic nightmare Him subjects us to for nearly its entire runtime does very little to earn our emotional investment. The movie is so busy manufacturing unease that it forgets to establish why any of this should matter to us in the first place. There is a scene early on meant to explain Cameron’s entire psychological framework: his father obsessively worships Isaiah White, projecting his own unfulfilled ambitions onto his son. It’s clean, efficient and dramatically inert.

Cameron barely interacts with his father in that scene. The man registers as just another unhinged football dad, a familiar archetype the movie assumes we’ll fill in emotionally on its behalf. Then the film jumps forward ten years, the father is dead, and Cameron has acquired the standard-issue, emotionally vacant personality of an elite football prospect. The trauma is implied and impossible to feel.

Tyriq Withers is fine. Arguably too fine. His performance is convincingly blank in the way real, highly successful underclassmen often are, people who have been insulated from introspection by constant validation and momentum. But that realism works against the movie. It’s hard to care about Cameron for the same reason it’s hard to care about any anonymous phenom whose life seems to function exactly as designed. Him asks us to fear what might happen to him without ever giving us a reason to hope for anything else.

*

Him is pretty much as bad as it was made out to be, which makes writing about it feel faintly redundant. Its most obvious flaws aren’t buried in subtext or ideology they’re structural and they all point back to an aggressive recut that reduced whatever this movie once was into something barely functional. Apparently, three different endings were shot, including two in which Cameron goes on to have a successful career despite having been brained, which means there are alternate versions of Him floating around in some hard drive purgatory.

None of them sound especially worth rescuing.

This isn’t a movie I’d recommend watching. But if you already did and walked away feeling confused, frustrated, or vaguely misled, take some comfort in this: your reaction is the correct one. Him doesn’t fail because it’s challenging or provocative, it fails because it’s compromised. If nothing else, this review exists to confirm that the movie didn’t work and that it wasn’t your fault. You’re not dumb for not getting it.

3.6/10

* Follow me on Instagram , Bluesky and Substack to keep up with new posts *