Book Review : Marlon James - A Brief History of Seven Killings (2014)

I have this theory about books that clear the 500–page mark: they’re designed to break you at least once. Not physically, but spiritually. Because if you need more than 400 pages to tell a story, it means you’re writing some kind of sprawling epic with rotating narrators, and statistically I’m going to despise at least one of them. And the moment that hatred kicks in, I’ll start spiraling like: what if the crucial clue to understanding the whole thing was hidden in that paragraph I skimmed while sighing on page 439?

It’s the same anxiety I used to have playing Baldur’s Gate II in 2003 knowing I just walked past a cave containing the sword that makes the rest of the game playable, but I can’t go back now. That’s exactly what happened when I finally pulled Marlon James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings out of the TBR pile it’s been haunting for years. Only difference is, the iconic, award-winning novel handled me a lot more gracefully than I handled it.

In case you’ve been living under a rock for the last decade, A Brief History of Seven Killings is a fictionalized account of the 1976 assassination attempt on Bob Marley. Some of you might not even know it happened, but in Jamaica it’s kind of a generational scar. Marlon James takes that moment and stretches it across a wide canvas: Kingston’s streets, CIA offices, Rolling Stone feature spreads, building a story that refuses to stay in one lane.

It isn’t just about the shooting itself, but the before, the during, and the long aftershocks, like a cultural earthquake that keeps sending tremors years after the initial jolt.

The Ectasy and the Agony of Being Politically Relevant

A Brief History of Seven Killings made me think about Taylor Swift, which is not what I expected when I cracked open a 700-page novel about Bob Marley and Jamaican politics. But hear me out: Swift spent the last two U.S. elections trying to convert her cultural relevance into political weight, and it mostly fizzled. Marley, on the other hand, actually had political weight, because he was a unifying figure in a country tearing itself apart. He stood for peace and unity in a place where the louder voices were nationalist and bloodthirsty.

He wasn’t playing the bipartisan game. He was playing something riskier, where the only outcomes are: make the world better, or wind up with a bullet in your chest.

That’s kind of what happens in A Brief History of Seven Killings. Marley, only ever referred to as "the singer", is less of a character and more of a gravitational force. He’s an inconvenience nobody can ignore, a spiritual speed bump for everyone with skin in the game: drug lords, politicians, CIA operatives. His music and his message don’t read as "peace and unity" to these people; they read as “problem.”

So the logic becomes: neutralize him. Shut him up. Get him out of the way. Which is how we end up with an assassination plot that feels like a badly scripted coup against hope itself, except it goes spectacularly right for one man in particular, gang leader Josey Wales, who walks away from the chaos with all the marbles (or almost).

As the novel trudges forward like a stubborn tugboat, A Brief History of Seven Killings makes a brutal point clear: every "empowering" feeling that’s ever been marketed to us under capitalism was never supposed to change a damn thing. Because real change would mean you stop buying, and the system can’t have that. James pulls at this thread relentlessly. Whether it’s political ideology packaged as salvation or cocaine packaged as escape, it’s all commerce, it’s all traffic.

Jamaica becomes the stage, but the play is universal: lives chewed up and traded as collateral in the name of profit. The result is a portrait that’s as glum as it is heartbroken. A coup against hope, carried out not with bullets alone but with the quiet grind of transactional cynicism. Taylor Swift might marry Travis Kelce and unite America behind her, it might just get her in the crosshairs. I don’t wish it on her, but if Marlon James made one thing clear with his novel is that there's not changing the self-destructive mechanisms of modernity.

Playing the Long Game

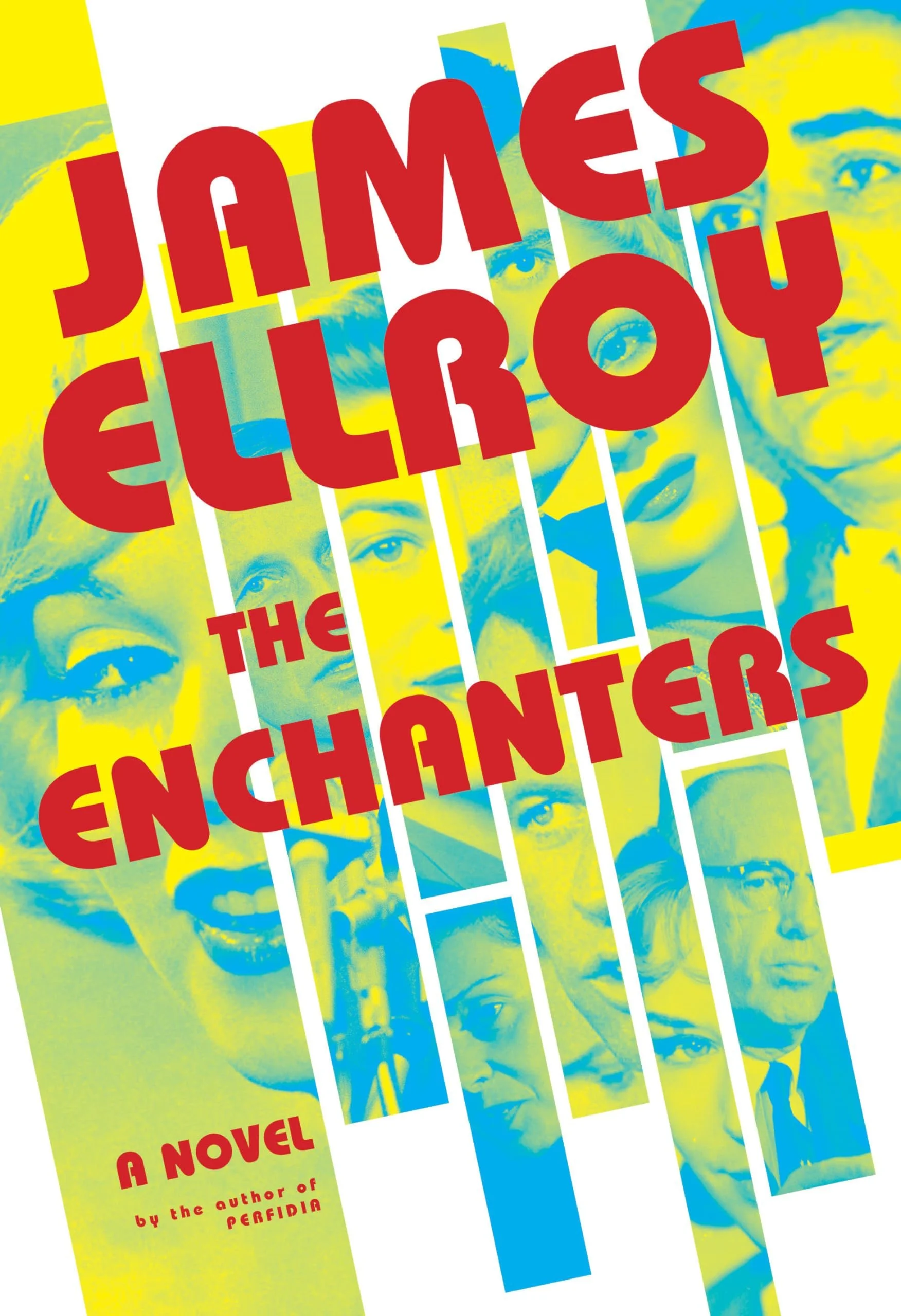

On a technical level, A Brief History of Seven Killings feels like Don Winslow’s cartel epics collided with William Faulkner, then dressed itself up in a tweed jacket and horn-rimmed glasses to remind you it’s also literary. It’s a lot. James juggles so many perspectives that, at times, the voices start bleeding together, especially the parade of Jamaican gangbangers who sometimes felt nterchangeable, like different actors reading from the same script.

It doesn’t sink the novel, but it nags at you. The way cold fries nag at you from the plate after you’re already full: you don’t want them, you don’t need them, but there they are, daring you to admit you’re tired of the taste.

But here’s the thing: James delivers. He builds this hulking geopolitical monolith that feels overbearing and unknowable for the first two-thirds, like you’re circling some giant machine with no idea of what it does. And then, almost casually, he starts connecting the wires. Those early chapters you thought were esoteric, maybe even skimmable? Suddenly they snap into focus. It’s not that you missed something; it’s that James was holding out on you.

The reveals land like a prank from a friend who’s been running a long con: cathartic, frustrating, and kind of hilarious once you realize you were set up. By the end, even the tiniest moments feel heavier, adding up to something larger, stranger, and more alive than you expected. And against all odds, it’s fun.

*

I had a good time with A Brief History of Seven Killings, and like most long novels I’ve enjoyed, I have absolutely no desire to ever read it again. Some experiences are meant to happen once, then calcify into memory where they’ll probably grow shinier, sharper, and more flattering than the reality ever was.

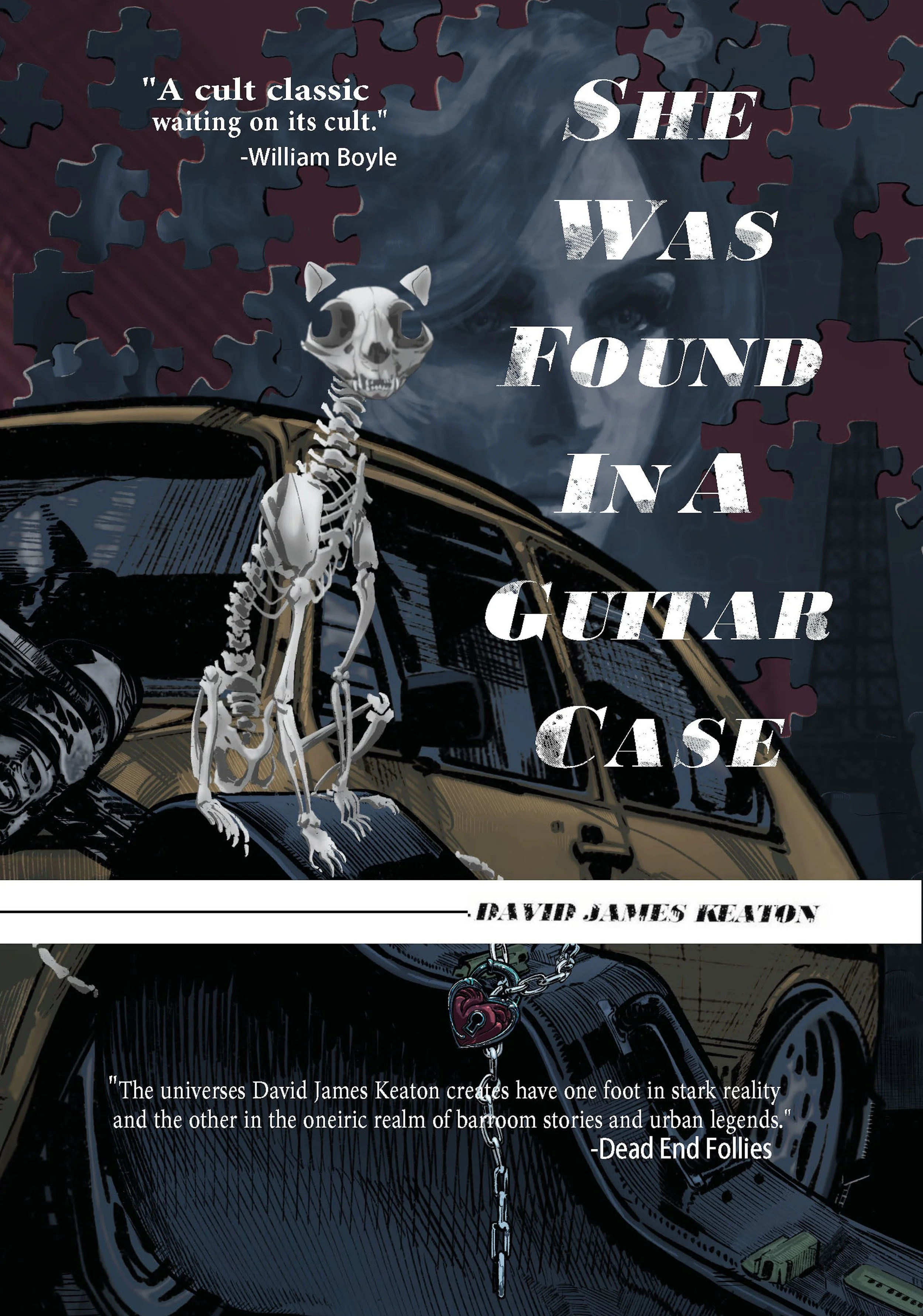

That feels fitting, because James isn’t just telling the story of a real crime; he’s tracing the way crimes mutate into folklore, into myth, into urban legends that take on lives of their own. The novel lives in that liminal space between fact and the stories we tell ourselves. And if it lingers in your head louder than it felt on the page, that’s not a flaw. That’s the point.

7.5/10

* Follow me on Instagram and Bluesky to keep up with new posts *