In The Beginning, There Was Sound: A Conversation With Anju Singh

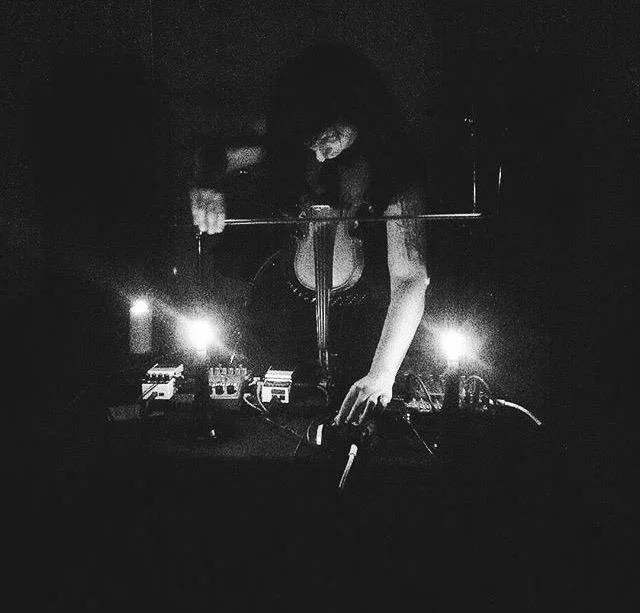

Credit: Emberlit Ethos

"Music is dead. It’s rules and theory and nothingness. Sound has embodiment. It means something."

I know exactly what Anju Singh is talking about. I’ve never picked up an instrument in my life, but I’ve spent years in practice rooms, headphones, venues, and fields feeling things. As far as I’m concerned, that makes me at least a qualified audience. Because what consistently moves me isn’t music. At least not the polite, boxed-up kind. It’s sound. The louder, the more raw and invasive, the better.

I mention how Brian Eno once realized the same thing. Back when he was still the synth guy in Roxy Music, he figured out he was more into sound than song. Anju lights up. She tells me she once took a masterclass with the ambient oracle himself. Right there is probably the reason why I'm a known enjoyer of her work. Anju Singh is, among other things, an experimental music artist performing under the name The Nausea.

"What makes musicians unique and important when AI can easily play perfect notes? It's that we maintain the human touch, we play the messy, wrong notes that carry feeling. The friction and texture in our playing. That’s our humanness."

The Nausea is Anju Singh’s violin-driven experimental project. I would call it a distant cousin to both harsh noise and film score, like they share blood but don’t talk much. I already have a soft spot for the violin when it’s played straight, so hearing it like this hit me right where it hurts.

For a while, Anju used to bristle when people called her music cinematic. But she’s come around. "I saw the term as manipulative at first, like it was trying to force a particular emotion. But I do like to tell stories. One without words that you can feel in your own way."

In other words: it’s still storytelling, but it belongs to whoever hears it.

Credit : Taylor Geddes

Artistry uncaged

If you’re trying to label Anju Singh, you’re already missing the point. In addition to composing as The Nausea, she plays in five extreme metal bands, works as a producer, she co-teaches workshops where people build their own instruments and maybe most important, a lifelong student. Anju refuses to be boxed in by what she does. “I can't stay in one thing and have it become my identity. I think I’d be really unhappy," she says.

Since volunteering at a media arts centre at 21, Anju has treated life like a rolling curriculum. "I didn’t realize that I was getting trained as a media and a sound artist right there and then. It changed my life," she says. Wherever she goes, she learns. Whether it’s computer networking at a radio station where she worked as a technical director, or design skills picked up as a junior graphic designer between tours. Every job, every side quest, becomes another node in the web. She follows the work, and the work keeps teaching her.

Although she never studied music in the traditional sense (she has a philosophy degree), Anju Singh’s work carved its own path into academia by sheer force of originality. Her drone-doom composition Neptune made the walls of the Centre D’Expérimentation Musicale rumble in Chicoutimi. “It’s an eighty-minute piece for seven musicians that takes you through a journey to the planet Neptune. From the Roman folklore to the planetary stuff.” You can sample it for yourself.

This creative boundlessness hasn’t just shaped her sound, it’s hardened her resolve to stay unbranded and unpredictacble . So many artists are branding themselves now. I think this is a social media thing. It makes you sell yourself as this one thing, you know. Fuck your brand. You just have to create from a place of pure authenticity."

That commitment to realness gave birth to Requiem, her 2024 album and personal Everest, one she spent a decade agonizing over. "Every single note on that record had some careful thought put in it. There's this song Purgatorium where there’s that one high note that goes through it all. For a whole year I wondered to myself whether or not that note should be there," she confessed. She left it in.

The song Abyssal Depth is another highlight off Requiem as it carries such a powerful melancholy, almost like a funeral dirge.

"This song I wrote for my own funeral," she confessed with a coy smile. That’s the closest I’ve seen her from being embarrassed. "See, I'm really afraid of drowning and I wrote this song after I decided to go swim in the ocean. I thought that I was going to die right there and then, so it seemed only fitting that I'd write my own funeral song. It's about a ship that sinks to the bottom of the ocean and comes to peace."

Initial Shock, Collaboration and The Future of Noise

I discovered The Nausea the way I discover half the noise and experimental acts I know: by obsessively scouring local show lineups. Anju was invited to co-headline local noise festival (we have a noise festival in Montreal and yes, it rules) Initial Shock with Richard Ramirez last year. I wasn’t even in town for it, but I still combed through every Bandcamp page on the bill like a truffle pig sniffing out distortion and dread. I know, I’m the audience any artist secretly wishes for.

“Initial Shock is curated with a lot of love and thought. It’s not a hype festival that tries to book the hottest artist at any cost. It’s built on belief and passion. They took a chance on me last year. I’m not the most popular artist out there and what I do isn’t necessarily what you’d expect at this kind of show," she says.

Anju and I met while she was in town to live score an old Japanese film with her violin, because of course she was. Just weeks earlier, she’d released Dream Disintegration, a collaborative record with First Nations artist Echthros, but there’s no tour, no PR blitz. For Anju, the project wasn’t about hype. It was about discovery. Another experiment in how to make music differently. "We did six tracks... two where we both started with no plan, two where he started, and two where I started. We wanted to see how it changed the result."

Colonial trauma was the shared vision that gave Dream Disintegration its center of gravity. "My parents were first generation immigrants. They were working all the time, trying to make it. So, they didn't tell me much about my heritage. I only came to understand South Asian colonial trauma as an adult, she says. The album’s emotional anchor is We Are What You Made Us a slow-burning act of resistance. "This album is exploring what it's like to be affected by this colonial machine and how we're moving through it."

Anju Singh will never make the music you want or expect her to make and that’s the point. She allows herself to be surprised, unsettled, and moved by wherever her creative vision leads. It’s not music in the traditional sense. It’s sound, shaped like a question. And if you’re listening closely, you’ll hear yourself answering back.

* Follow me on Instagram and Bluesky to keep up with new posts *