Movie Review : The First Power (1990)

People forget this now, but there was once an era where reality did not come pre-fact checked or optimized for comprehension. Before the Internet transformed doubt into a renewable resource, the world operated on ambient confusion. Everything was approximately 25% scarier because everything was 25% more unknowable. AIDS lived in the same mental category as serial killers, Satanic cults, poisoned Halloween candy, and whatever frightening rumor was circulating at your local bowling alley.

Probability didn’t matter. Authentic threats and imaginary curses were given the exact same narrative authority. It’s basically how my mom decided what I could and couldn’t do even if we lived in the dead end of the world where nothing ever happened outside of domestic violence. That’s the world that made a movie like Robert Resnikoff’s The First Power possible, a cinematic artifact from a culture that treated fear like a public utility. Its mere existence feels like the most convincing special effect in the entire film.

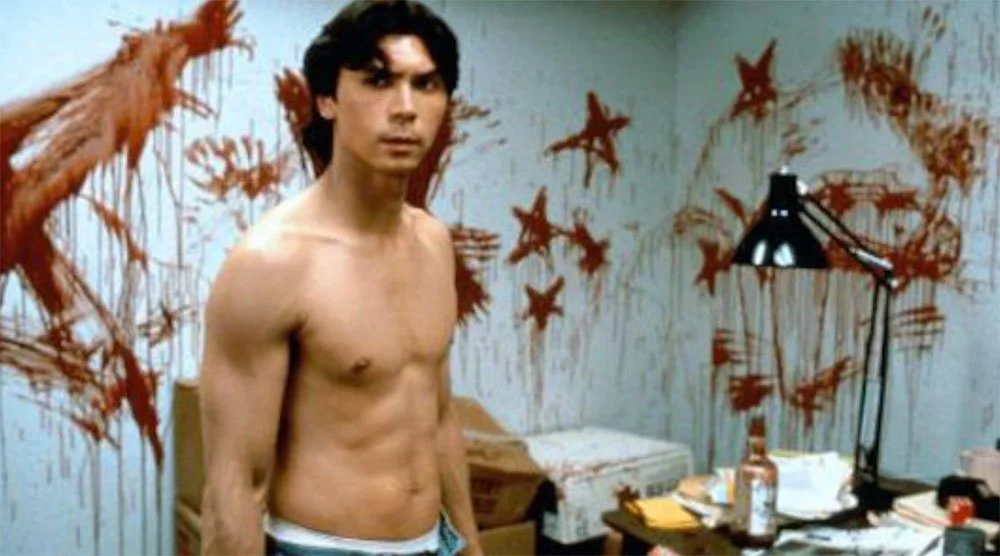

The First Power is loosely inspired by the Richard Ramirez mythos: the idea of a serial killer so committed to evil he might actually have accrued frequent-flyer miles in Hell. Lou Diamond Phillips plays LAPD detective Russell Logan, a juvenile cop who feels morally obligated to out-crazy the crazy. He manages to catch Patrick Channing (played by perpetual cinematic nightmare Jeff Kober) and sentences him to the gas chamber. Justice appears to win for about six minutes.

Then Channing comes back, apparently immune to physics, mortality, or the concept of narrative closure. He kills with the giddy persistence of a kid refusing to leave the carnival just because the fairground lights are shutting off. The movie treats supernatural murder like a form of recreational recidivism and I mean that in the best way possible.

The Sweet Taste of No Accountability

The First Power is not a good movie in the conventional sense, yet it radiates such reckless self-assurance that you’re hypnotized anyway. It’s the cinematic equivalent of the guy at the bar who insists he’s irresistible, and you start believing him out of sheer exposure to his certainty. The film’s audacity becomes a weird virtue. Those early scenes where Channing returns from the dead (half hallucination, half supernatural jailbreak) play like they’re cheating at storytelling and simultaneously discovering a new form of terror.

The movie keeps staging events with an unapologetic straight face, then restaging them as if reality simply rebooted itself and deleted all trace of Channing’s previous crimes. It’s reckless, confusing, and unexpectedly convincing.

If you grew up in the 90s, The First Power feels spiritually aligned with those deranged CD-ROM horror games: Phantasmagoria, Hopkins FBI, every low-budget point-and-click fever dream where the developer clearly had total freedom and zero adult supervision. There was a whole era when entertainment didn’t answer to anyone, so it compensated by being aggressively earnest and profoundly unhinged. That’s the wavelength this movie operates on.

It has an improvisational gravitas that feels like the plot is being written in real time by someone who isn’t fully convinced they understand how movies work. At one point, Logan and his psychic love interest Tess (Tracy Griffith) are fleeing Channing, and he rips the ceiling fan off the roof and starts pursuing them with it, like an improvised murder prop from a parallel dimension. And the fan sequence keeps going. I don’t think I’ve ever seen this visual logic in any other movie, except maybe the fictional knockoff action films Bart watches on The Simpsons.

It’s both ludicrous and oddly sincere, which somehow makes it unforgettable. I have no idea how someone of sound mind and body has greenlit this, but I’m glad they did.

Incompetence As Art

There are countless moments in The First Power that shouldn’t function on any cinematic level, and yet they do. Patrick Channing’s murders are patently absurd, but because he’s effectively operating as a demon, they land in that uncanny limbo between realism and spectacle — where disbelief isn’t suspended so much as force-fed into submission. At one point he crucifies a cop fifty feet in the air under an overpass. There is no logistical or supernatural explanation that satisfies this image.

You can’t reverse-engineer the physics of it, even if you accept the premise of a resurrected killer. But that’s not the question the movie is asking. The important thing is that a professional guardian of public safety has been rag-dolled and displayed like a warning from a cosmic intelligence you don’t understand. The First Power refuses to tell you whether to be horrified or amused, and (against all common sense) it’s more compelling because it denies you emotional clarity.

Detective Logan has no business solving any of this. He’s essentially a teenage edgelord occupying the body of a public servant, powered less by investigative skill than by his inability to regulate his most juvenile impulses. Like every fictional (and non-fictional) cop who misunderstands his own job, Logan wants a suspect who fits the narrative in his head and isn’t particularly interested in the messy details of reality.

He talks too loud, escalates every situation, burns energy chasing theatrical dead ends, and behaves in ways that would get a normal officer reassigned to desk duty for the rest of his life. But none of that really matters. What matters is that we’re watching a man whose only qualification is that he’s been tasked with confronting evil. In a pre-internet world where the boundaries of possibility were wide open, we didn’t need the right person in charge, we just needed someone to absorb the responsibility.

The identity was irrelevant. Authority against evil was the fantasy.

*

The First Power sits at a humble 5.7 on IMDb, but that rating is a statistical failure to measure the value of chaos. Its insanity isn’t a flaw, it’s the feature. This was made in the pre-Cobain nineties, when America still clung to the idea that there were good guys and bad guys, and being the bad guy wasn’t considered aspirational or anti-hero chic. The movie makes no effort to explain itself, and maybe that’s why it feels so potent now.

If you lived through the era when television would broadcast anything, urban legends, Satanic Panic PSAs, serial killer coverage that bordered on fan service, this film hits a nostalgia gland you didn’t realize you had. It reminds us of a time when culture wasn’t self-aware or ironic about its own stupidity. Nobody is making movies like this anymore, and maybe nobody can. That’s what makes it special: it’s a relic from a reality that no longer believes in itself, preserved on film like a warning or a dare.

7.5/10

* Follow me on Instagram and Bluesky to keep up with new posts *