Movie Review : Train Dreams (2025)

Any socially healthy adult will deny this, but life will eventually remind you — repeatedly, casually, and without malice — that it’s a lie: we all believe we’re the most important person in the world. Not in an Instagram way. Not as a symptom of contemporary entitlement. It feels older than that, more structural. Like a design flaw etched into consciousness itself. The mistake isn’t believing it. The mistake is assuming it matters.

What defines us isn’t our importance, real or imagined, but how we behave once the universe proves that it will keep going without our input. Life doesn’t wait for you to swallow that realization. It just keeps hacking away.

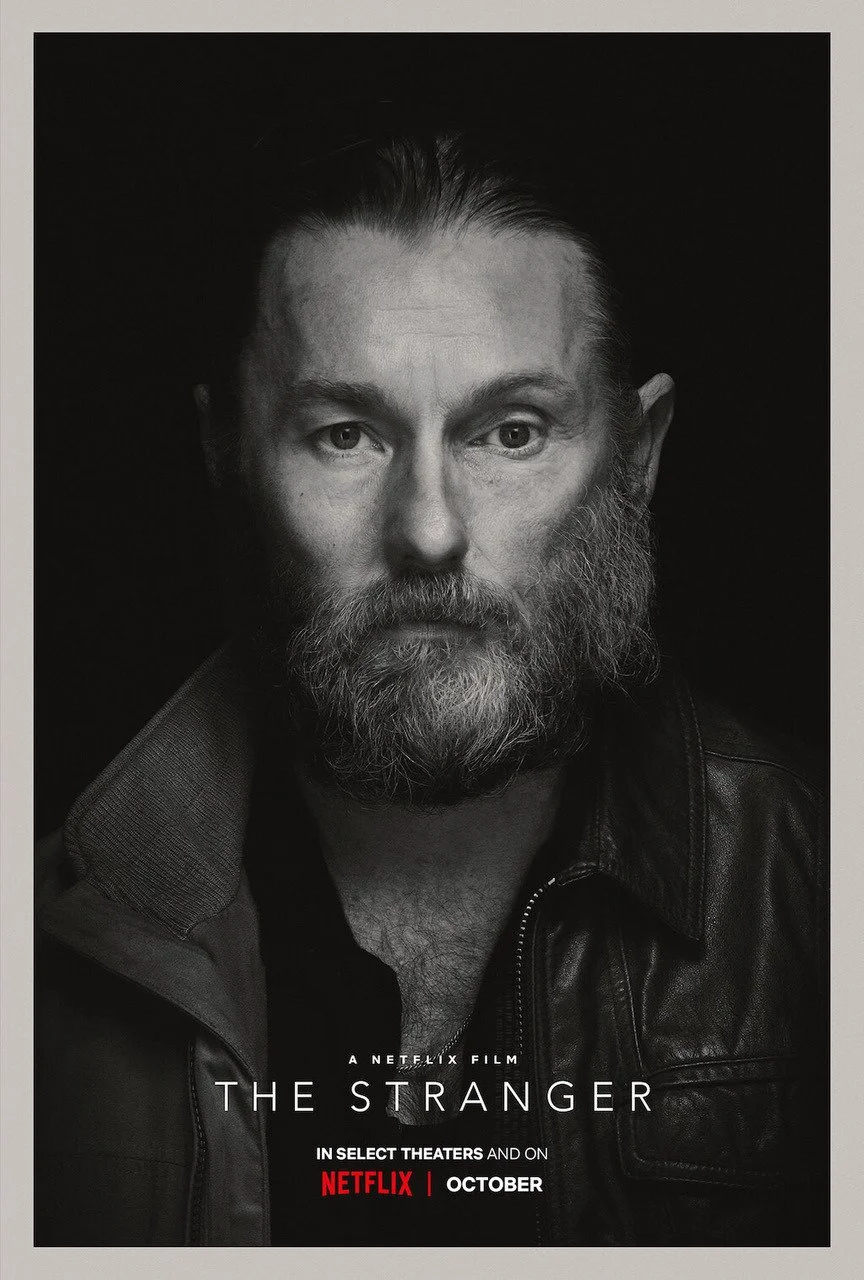

What makes the protagonist of Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams (and its susequent Netflix adaptation) Robert Grainier (Joel Edgerton) unusual is that he never developed a real sense of self. He simply exists, contributes to history in small, tangible ways, and then disappears into it completely.

Train Dreams follows Grainier, a quiet, anonymous railroad worker who goes wherever the work happens to be. He falls in love with a young woman (Felicity Jones), has a child with her, and builds them a home meant to hold the parts of his life he can’t carry with him. When a senseless tragedy takes both away, the story refuses the expected arc. Grainer doesn’t self-destruct. He doesn’t spiral into spectacle. He doesn’t become tragic in the way narratives usually require.

He just keeps living: damaged, altered, permanently misaligned, moving through the world as someone searching for meaning without ever insisting it owes him an answer.

Man's Search For Meaning

Train Dreams is a beautiful film, though not in the now-standard way where a drone glides over Pacific Northwest forests until everything starts to resemble a Patagonia ad. That kind of beauty is decorative. This film’s beauty is colder and more unsettling. The landscape gives Robert Grainier everything he will ever have and takes it all away without ever acknowledging that he was there. It doesn’t oppose him. It doesn’t judge him. It simply continues. The same is true for the railroad workers carving paths through it and Robert keeps trying to situate himself inside this indifference because he never learned how to imagine a life that exists outside of it.

There is no inherent meaning in Robert’s relationship to nature, and over time, through age, repetition, and loss, he stops pretending that there should be. He accepts his place as a functioning part in a system too large to care whether he understands it. The film quietly proposes that this might be enough. That being of use can substitute for being important.

When the people who once gave his life emotional gravity disappear, Robert stops asserting himself against the world. Others drift in and out, propelled by appetite, ambition, or selfish necessity, while he remains: coping with loneliness by forgiving the indifference that caused it, as if resistance would only make things worse.

This is why Robert Grainier’s life feels both unremarkable and strangely emblematic of how civilizations are actually built: through acts of self-sacrifice so complete they don’t even feel like sacrifices to the people making them. His life contains beauty, incident, and even tragedy, assuming you’re willing to meet it with a baseline level of human compassion. Train Dreams treats loss and death as structural facts, not narrative emergencies. There is no demand to rage against them, only to live around them. That seriousness is faintly disturbing, but it’s also comforting. The film insists (almost stubbornly) that a quiet, "meaningless" life can still be complete, still valid, and still worthy of being lived.

A Quiet Death Called Progress

Another fascinating aspect of Train Dreams is the period Robert Grainier happens to live through. Early twentieth-century America is defined by acceleration: railroads, cities, systems arriving faster than individuals can emotionally recalibrate. Robert begins his life shaped by wilderness labor and ends it surrounded by forms of modernity that were never designed to notice him.

There’s a quiet cruelty in the fact that Robert helps build the very symbol of American progress that will eventually render him obsolete. The railroad is a mechanism that carries the future past him without slowing down. By the time modern life fully arrives, Robert is already an artifact of the world it replaced.

Yet progress doesn’t only erase Robert, it also anesthetizes him. As the world modernizes, his earlier life fades into something distant and indistinct and with it the sharpness of his grief. What replaces meaning is a kind of emotional stasis. The future doesn’t save him, but it dulls the pain of what he’s lost, which may be the most generous thing progress ever offers him. Robert humbly finds solace in the beauty that is still left.

This humility sits at the core of what makes Robert Grainier such a quietly compelling character. Though he speaks little, he is not empty. He is a discreet thinker who happens to be born at the wrong moment to fully exercise his capacities, working through his place in the world using the limited language his era affords him. Robert rarely shares these thoughts with anyone. Instead, he cultivates them privately, assembling an inner life from observation, memory, and silence. Over time, that interior world becomes sufficient. Not triumphant. Not enlightening. Simply enough to sustain him.

This isn’t the kind of outcome people who believe themselves to be exceptional are trained to admire. It offers no validation, no recognition, no upward trajectory. And yet, there is something deeply respectable about the self-sufficiency Robert earns, not through denial or repression, but through acceptance. He doesn’t transcend the world. He learns how to live inside it.

*

I didn’t expect to like Train Dreams as much as I did, and a half-conscious part of me suspects that’s because (like most people) I still believe I’m the most important person in the world. Culture insists otherwise, of course, but that belief never really disappears. It just goes quiet. The problem isn’t that there shouldn’t be a most important person. It’s that importance is supposed to be a choice, defined by what you decide to pay attention to and who you decide to give your time to.

For two hours, Robert Grainier becomes the center of the universe, and it somehow feels earned. Not because he demands attention, but because he never looks for it. He isn’t busy curating himself, explaining himself, or insisting on his own significance. He just exists, and the film agrees to meet him there. That might be the most persuasive argument Train Dreams makes: meaning doesn’t come from believing you matter, it comes from learning how to look away from yourself long enough for something else to take focus.

8.2/10

* Follow me on Instagram , Bluesky and Substack to keep up with new posts *