Movie Review : Skinamarink (2023)

The scariest place for a child is his own home. This feels counterintuitive, mostly because adults have been conditioned to see "home" as a synonym for safety. But for kids, it’s different. It’s not just where they live. It’s all they know. Before school introduces them to the slow-drip horror of social comparison, the house is the entire universe. And since their brains aren’t yet overrun with adult abstractions like "context" or "tax brackets," they’re unusually sensitive to environmental inconsistencies.

They don’t remember last week. They don’t plan for tomorrow. Everything they experience is happening now, and it either makes sense or it doesn’t. That’s why haunted house stories never really go away. They just adjust to the broadband era. And Skinamarink might be the first one that truly understands the way fear works when you’re four years old and the floor plan of your life starts to glitch.

Skinamarink is a Canadian experimental horror film, though "film" feels like a stretch, and "horror" only works if you’re thinking metaphysically. It sort of tells the story of a four-year-old boy named Kevin and his six-year-old sister, Kaylee, who experience a sequence of inexplicable events in their home over the course of an indeterminate night. First, their father disappears. Then the windows. Then the doors. Eventually there’s a chair on the ceiling, because of course there is.

Something’s clearly wrong, but there’s no one around to explain it. Not to the characters, and certainly not to us. And this isn’t one of those movies where childlike imagination saves the day. There is no day to save. There's just this looping, low-resolution nightmare that feels like trying to remember something that never made sense in the first place.

Absence makes the heart grow fucking terrified

Skinamarink writer-director Kyle Edward Ball has name-dropped Chantal Akerman and Michael Snow’s Wavelength as major influences, which is the kind of statement that instantly separates the audience into two camps : people who nod knowingly, and people who Google "Wavelength movie explained" and immediately regret it. It gave me just enough prep to know what I was in for. This isn’t a "watching a movie" experience. It’s more like being gently suffocated by the idea of a movie.

Skinamarink is enthusiastically minimalist in the same way Joe Rogan is enthusiastically into meat: there’s nothing ironic about it, and it might actually be dangerous if taken too literally. It’s committed, almost ravenously so. The film operates under a guiding principle that horror fans intuitively understand but rarely articulate: the less you’re told, the more your brain panics to fill the gaps. Ambiguity is an accelerant. If you’re afraid of the dark, it’s not because darkness contains anything specific. It’s because it could contain anything.

Mostly whatever it is you’re afraid of.

As Kevin and Kaylee drift through the dim void of their suburban house, the audience is granted flashes of.. something. Not answers, just fragments. The camera often hovers low to the ground or tilts upward at strange angles, replicating what a child might actually see, which turns familiar spaces into geometric riddles. Silence, which should be comforting in a domestic setting, instead becomes a form of psychological static. There’s no score. No exposition. Just the hum of absence, which somehow amplifies the presence of whatever isn’t supposed to be there.

And that’s real horror. Not monsters, not gore, not jump scares, but the realization that you’re inside something unknowable, and no one is coming to explain it. Skinamarink barely touches traditional haunted house tropes. Instead, it offers dislocated images and incomplete moments, trapping you in a consciousness that’s pre-linguistic and helpless. It doesn’t scare you with things that go bump in the night. It scares you by taking away your tools for interpreting the bump at all. There’s no catharsis here. Just dread that stretches out like a hallway that wasn’t there yesterday.

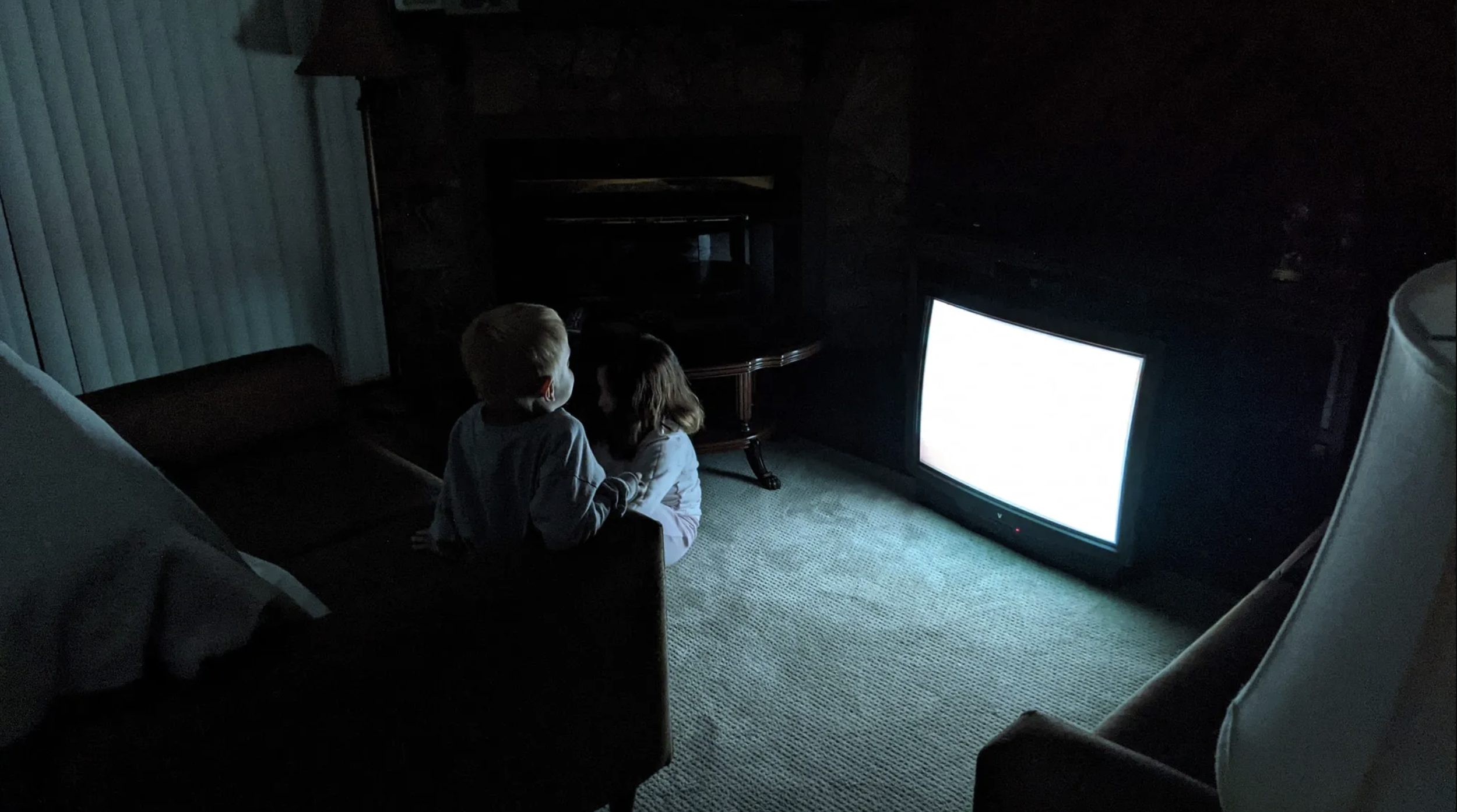

We all saw the TV fucking TV glow, goddamnit

Roughly eighty percent of Skinamarink’s lighting comes from the pale, flickering glow of old-school tube televisions and it absolutely rules. The entire house is soaked in that washed-out blue-white aura that used to mean comfort, or boredom, or background noise. Here, it feels like the final light source before reality folds in on itself. It’s totally rational, Kevin and Kaylee are watching cartoons in the dark, but that doesn’t make it any less unsettling. The implication is clear: they could turn the lights on, but they don’t.

Maybe they know, instinctively, that they’re not supposed to.

Because that’s the logic of Skinamarink. It doesn’t follow dream logic or nightmare logic, it follows kid logic first and foremost. And by that I mean the unspoken rules you somehow just understand when you’re four years old. The house at night isn’t supposed to exist. The rooms shouldn’t look like this. You’re not supposed to be awake, and you’re definitely not supposed to be wandering. And while the film never explicitly says so, it feels like their presence in this nighttime dimension, the fact that they see what they’re not meant to see, is what accelerates the house’s collapse. Like they’ve triggered something by staying up too late. The punishment isn’t immediate. It just keeps getting worse.

Kevin and Kaylee are too young, too scared, and too preoccupied with the disappearance of their father to fully comprehend what’s happening. Which leaves you, the viewer, as the only party aware enough to feel the full weight of their transgression. You’re not just watching two kids get swallowed by a haunted house. You’re watching them get swallowed by the cosmic consequences of disobedience, by a kind of metaphysical parental disappointment that can’t be soothed with a lullaby or a nightlight.

*

Skinamarink is less a movie than a sense-memory trap. It’s a sensory experience masquerading as visual storytelling. It doesn’t ask you to "relate" to Kevin and Kaylee, it reverts you into them. Most films with child protagonists assume you’ll project yourself into the character. This one strips you of that option. You are the child, helpless and disoriented, trying to decode a house that no longer abides by physics or bedtime rules. You won’t get answers. You won’t connect the dots. What you’ll get instead is the weird, persistent feeling that some part of your childhood looked exactly like this and that you just forgot until now.

I can’t think of a higher calling for horror.

8.2/10

* Follow me on Instagram and Bluesky to keep up with new posts *